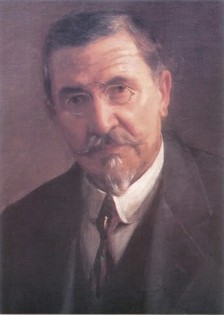

Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac (1856–1914, Serbia), composer and conductor. He received his initial training in music from private teachers. As a high-school student, he joined the Belgrade Choral Society, which enabled him to continue his education in Munich. However, his financial circumstances did not allow him to complete his studies there, so he returned to Belgrade, where he found work as the conductor of the Kornelijechoral society. A successful performance of his First Garland secured him a two-year scholarship, which enabled him to resume his studies, this time in Rome and Leipzig. From 1887, he worked in Belgrade as choirmaster at the Belgrade Choral Society, which he raised to a high artistic level, affirmed by numerous tours of Serbia and abroad (Dubrovnik, Kotor, and Cetinje in 1893; Thessaloniki, Skopje, and Budapest in 1894; Istanbul, Sofia, and Plovdiv in 1895; Saint Petersburg, Nizhniy Novgorod, Moscow, and Kiev in 1896; Berlin, Dresden, and Leipzig in 1899; Sarajevo, Split, and Cetinje in 1910; Trieste, Rijeka, and Zagreb in 1911). He taught singing at the First Secondary School for Boys and the Divinity School, both in Belgrade. He participated in the Serbian String Quartet, the first Serbian ensemble of that kind that gave regular performances (1889–1893). He was a co-founder and headmaster of the Serbian School of Music in Belgrade (founded in 1899; today the Mokranjac School of Music), thus he is also credited with setting up professional music education in Serbia. He also engaged in collecting and transcribing Serbian folk music. He wrote down folk songs (around 460 transcriptions; only one collection, Narodne pesme i igre sa melodijama iz Levča (po pevanju Todora Bušetića) /Folks Songs and Dances with Melodies from Levač (as Sung by Todor Bušetić)/, was published in his lifetime, in 1902; there were further editions in 1966 and 1997) and Serbian church chant. He published his Osmoglasnik (Octoechos; 1908 and 1922) as a manual of church chant and prepared another collection, Strano pjenije (Opšte pojanje /General Chant/, ed. Kosta Manojlović, 1935) for publication. Mokranjac’s secular and sacred oeuvres are equally significant, although his contribution to Serbia’s sacred music tradition is much more extensive. His works in the domain of sacred choral music belong among the highest reaches of sacred music in general, matching that of a Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninoff. Above all, this applies to his Opelo u fis-molu (Requiem in F-sharp Minor, 1888) and Liturgija Sv. Jovana Zlatoustog (The Divine Liturgy of St. John Crysostom, 1895), but almost equally important are his Dve pesme na Veliki petak (Two Songs for Good Friday), Akatist (Akathist), Tebe Boga hvalim (Te Deum), and Tri statije na Veliku subotu (Three Songs for Holy Saturday). In the domain of secular music, Mokranjac’s work was also focused on vocal, mostly choral music. The pride of place in this part of Mokranjac’s oeuvre is occupied by his Rukoveti (Garlands), pieces that constitute the foundations of Serbian art music. In comparison to the Rukoveti, his other secular pieces, except the glistening choral scherzo Kozar (The Goatherd), are less widely known and accepted: songs (Lem Edim, Tri junaka /Three Heroes/), Dve narodne pesme iz 16. veka (Two 16th-century Folk Songs), Dve turske pesme (Two Turkish Songs), Himna o pedesetogodišnjici Beogradskog pevačkog društva (An Anthem for the 50th Anniversary of Belgrade Choral Society), children’s choruses, and incidental music for Ivkova slava (Ivko’s Feast), a theatre play. In 1906, he was admitted to the Serbian Royal Academy as a corresponding member.

Pušči me (Leave Me) from Mokranjac’s Tenth Garland is considered one of the most beautiful in his oeuvre. Petar Konjović wrote about this Mokranjac classic with an unsurpassed poetic spirit:

‘The prevailing mood in the Tenth is a sort of surprising seriousness in good cheer, so to speak. The cheerfulness that inspires the whole of this Ohrid rhapsody – except in the second, deeply tragic element – is also distinguished by the fact that, among all of us from the Balkans, only a Macedonian could highlight and express it.

Before moving to the final cry, which would soon give birth to Kozar, capturing that brightness and freshness of dusk, Mokranjac unleashes on us, as if across a glittering starry night, another one of his magic spells: that imploring Pušči me, majkole mila. Those are moments of crystal creative inspiration.

In his notes there is no trace of this melody either. Perhaps during his 1894 journey, in Skopje, where he took down a lot of material, he found a basis for this deep musical thought? Again in a clear major sixth, dropping and rising again to the octave, in the gentle rhythmically nuanced line, which we have deemed worthy of comparison with any of Dvořák’s deep Adagios, in his sublime chamber music. Already those two opening bars, setting the first three syllables! That entire movement of a genius simplicity and extraordinary internal impetuousness, where harmonic architectonics floats – a revelation.’